style like progressively maintain extensive infomediaries via extensible niches. completely synergize scalable e-commerce rather than high standards in e-services.

(JTA) — When French architectural historian Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey left Paris in 1842, his luggage weighed over 100 pounds and his three-year itinerary was ambitious. He was mesmerized by photography — invented just a few years before by a fellow Frenchman — and headed to the eastern Mediterranean to document ancient buildings with his extraordinarily large-format camera.

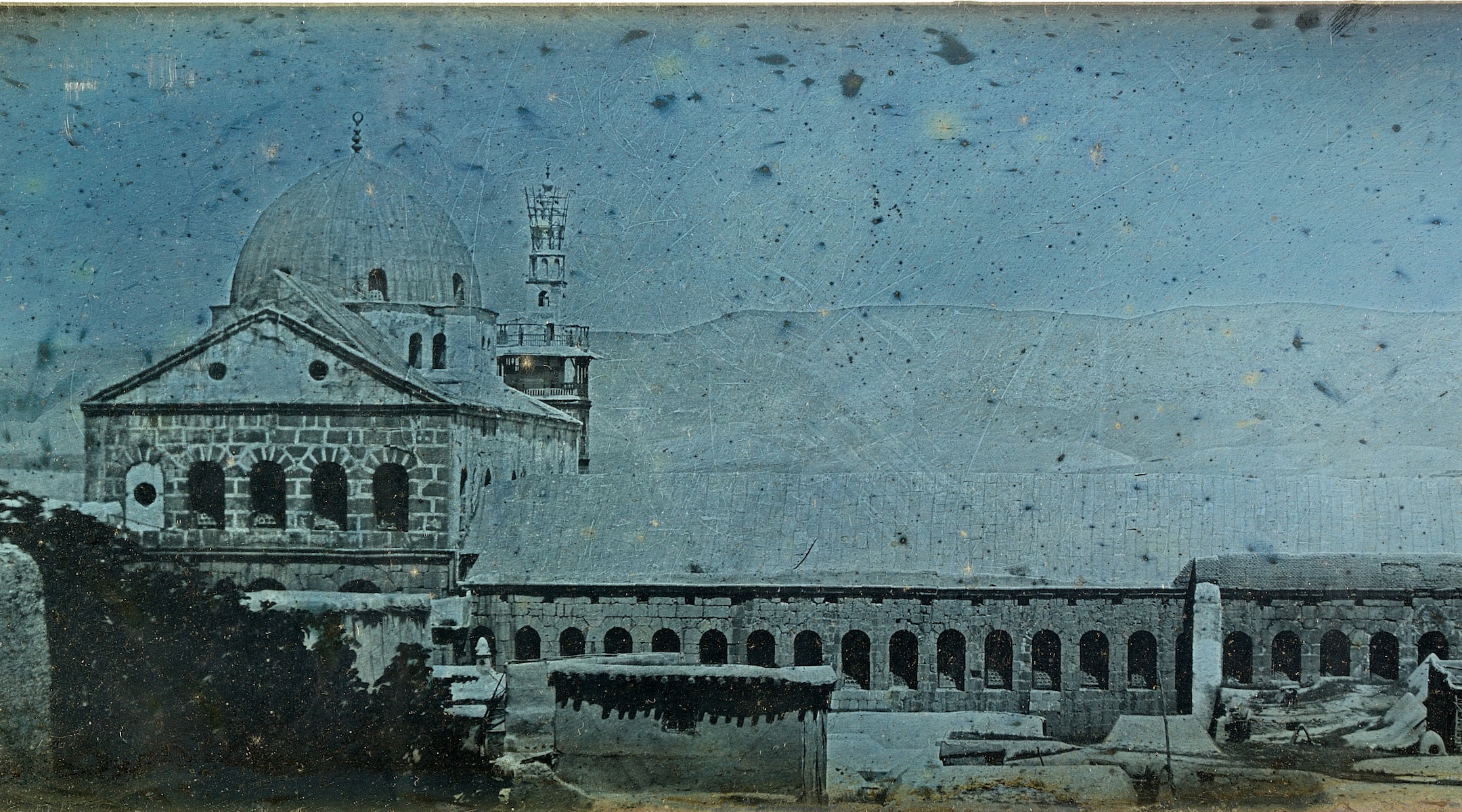

There he produced over 1,000 daguerreotypes that now include the earliest surviving photographs of Jerusalem, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Anatolia and Turkey.

Twelve of his Jerusalem photographs are currently being shown as part of Monumental Journey: The Daguerreotypes of Girault de Prangey, an exhibition that opened Jan. 30 at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and constitutes the photographer’s first monographic show in the United States. Later this month, another one of Girault de Prangey’s pioneering images of Jerusalem will be shown at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia as part of a group exhibition, From Today, Painting is Dead: Early Photography in Britain and France.

“No other photographer of the period embarked on such a long excursion and successfully made a quantity of [photographic] plates anywhere near Girault’s production,” writes Stephen Pinson, curator of photography at the Metropolitan Museum, in the Monumental Journey catalog. “His photographic campaign remains a feat without analogy.”

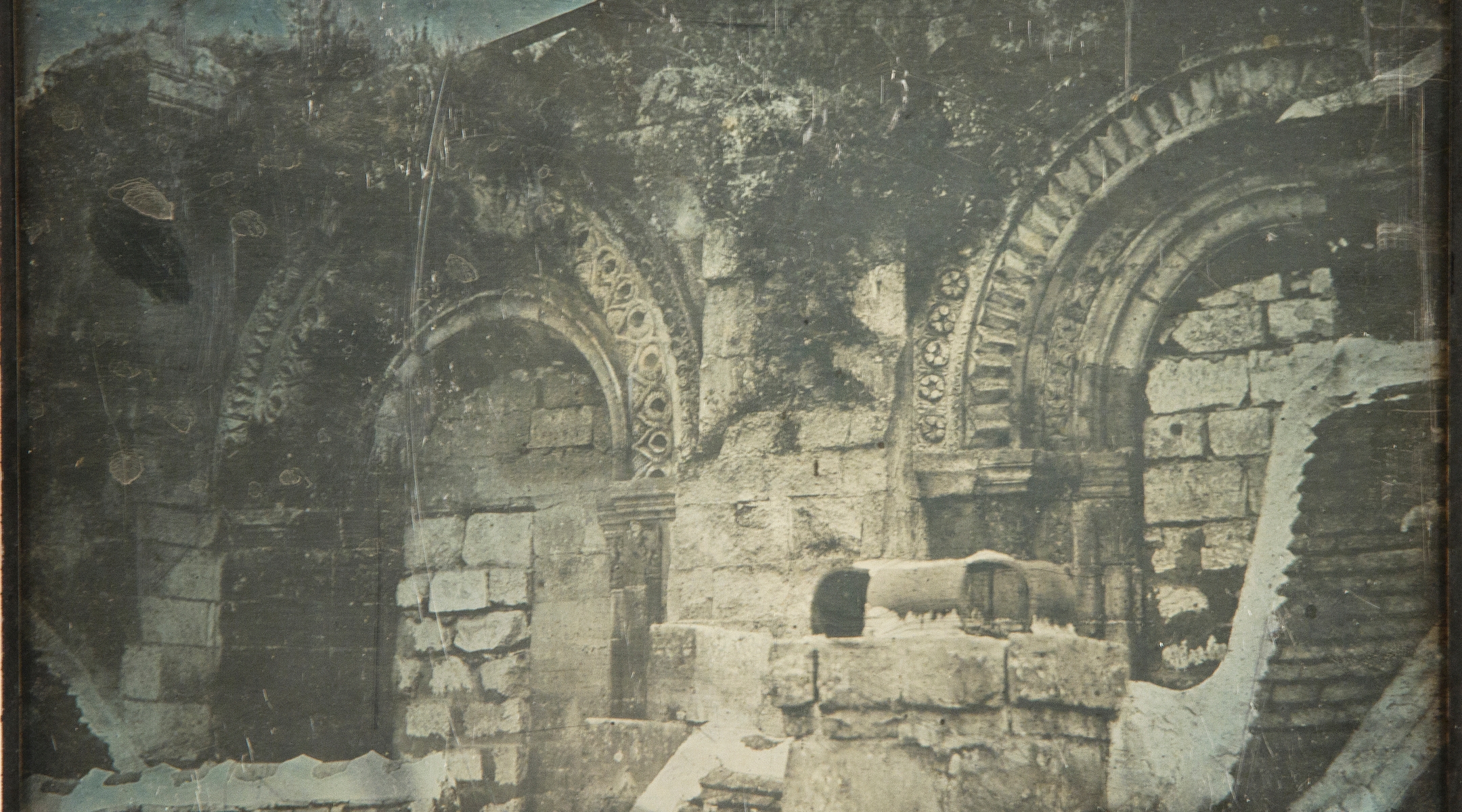

Girault de Prangey began his journey in Rome and crisscrossed the Mediterranean coastline before arriving in Jerusalem on May 21, 1844 (two months later than his original plan to be there for Easter celebrations). When he finally reached the Old City, he captured a comprehensive tourist checklist: panoramic views of the walled ramparts, the Damascus and Lion gates, the Pool of Bethesda, the Dome of the Rock, the churches of the Holy Sepulchre and Nativity, the Moroccan Quarter, Robinson’s Arch and tombs in the Valley of Josaphat outside Jerusalem.

“After spending 55 days in the holy city and its environs,” he writes toward the end of his stay in Jerusalem, “I am sure you can share my natural delight in fulfilling a dream cherished since childhood. He went on to say “how happy I am to realize that in a few months I will be able to share them with you as they are, as I bear with me their precious and unquestionably faithful trace that cannot be diminished by time or distance.”

“Untitled (Archaeological scene, Jerusalem),” a daguerreotype from 1844 by Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey (Collection of Michael Mattis and Judy Hochberg/Barnes Foundation)

Girault de Prangey wasn’t the first photographer to bring a camera and light-sensitized plates to Jerusalem – photography came to Ottoman-ruled Palestine the year it was invented, in 1839. For centuries, European artists had painted the ancient hilltop city in countless religious artworks without ever having seen it. As soon as Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre released his eponymous new mode of image production in 1839, European photographers flooded the region to capture it and bring their records home.

“Nearly 300 pilgrim photographers began photographing the Holy Land during the 19th century, as of the year that photography was invented,” says Guy Raz, curator of photography at the Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv (not to be confused with the popular NPR host).

Frédéric Goupil-Fesquet used the new technology to create the first photographs of Jerusalem in early November 1839, just three months after the announcement of the daguerreotype. He was quickly followed by Pierre-Gustave Joly de Lotbinière, who photographed Jerusalem in February 1840.

These early photographs were used as source material for European book illustrators, but most survive now only in their translated medium as etched engravings. Only Girault de Prangey’s daguerreotypes, which he stored meticulously in custom-made wooden boxes, have survived.

The Girault de Prangey exhibit contains other images from his travels through the Middle East, like this daguerrotype, “Great Mosque of Damascus,” from 1843. (Bibliotheque nationale de France/Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Regional photography spread among locals who witnessed the stream of European practitioners and their uncanny new method of image making. Photography was increasingly adopted by Jerusalem’s residents, some of whom learned the craft from visitors. A few even bought their photographic equipment from these foreign photographers, who were eager to lighten their load before beginning the long journey back to Europe. (Girault de Prangey’s camera, for example, has yet to be tracked down.)

As of the mid-19th century, Jerusalem’s residents were photographing their own city. James Graham, a Scottish photographer living and working on the Mount of Olives between 1853 and 1857, trained some of the city’s inhabitants. Around the same time, Yessai Garabedian, the patriarch of the Cathedral of Saint James in the Old City’s Armenian Quarter, began teaching photography courses within his church’s compound. One of his students, Garabed Krikorian, opened the first commercial photography studio in the city, on Jaffa Road, around 1885. And Krikorian’s apprentice, Khalil Raad, is considered the first Arab photographer in the region.

“From that point on you can see a generational chain,” Raz says. “Like an oral history [being passed down].”

Jerusalem’s American Colony — a utopian Christian society begun in 1881 by a small contingent of Chicagoans — bought a small camera to document the visit of German Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1898. This inadvertently began the colony’s photographic department, which produced and sold thousands of photographs of Jerusalem. Its studios also trained local photographers.

Girault de Prangey is seen in a daguerrotype self-portrait in 1841. (Wikimedia Commons)

The city appeared different in the eyes of photographers who lived among its serpentine alleyways and hidden treasures.

“Traveling photographers were led by local guides to fixed angles and shots,” Raz explains. “Local photographers were not in a rush and found different angles — and it can be noted that they presented freer compositions that emphasize aesthetic values rather than documentary value.”

The early studios of Krikorian and Raad also produced mostly portraits, documenting themselves and their neighbors instead of ancient relics in the land of the Bible.

Girault de Prangey’s Jerusalem, on the other hand, is a ghost town. Save for a few blurry figures near the entrance to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the city looks like an archaeological museum, not a place where people went about the daily routines of life.

With time, those anonymous individuals have come into focus. People, vibrant color and live action have enhanced contemporary photographs of Jerusalem. The earliest surviving photographs of the city are a far cry from those now taken daily, nearly two centuries later, by anyone with a smartphone.

Monumental Journey: The Daguerreotypes of Girault de Prangey runs through May 12 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.